Owning a pocket knife meant adulthood in my corner of The Bronx. And no knife carried more street cachet among members of my tribe than the K55 gravity knife.

Owning a pocket knife meant adulthood in my corner of The Bronx. And no knife carried more street cachet among members of my tribe than the K55 gravity knife.

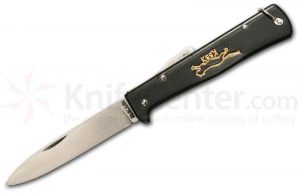

They were balanced. They were slim. They were sharp. They flicked open with a snap of the wrist, once broken in. And they looked serious. Very serious.

We kids were K55 connoisseurs. Only the German-made version — with the iconic panther outlined on the handle in gold — would do. These were far superior in quality to the Japanese-made K55s, which had the telltale marking of the gold-outlined panther with stripes. The Japanese K55s had malfunctioning locks, and rivets that loosened far too easily.

Pre-teens could not, technically, purchase knives such as the K55 on their own. However, we knew that one store on Fordham Road, the crowded, hilly, shopping strip that snaked from the Harlem River to Southern Boulevard and that served as our 60s-era mall, would sell knives to virtually anyone. Even eleven-year old kids.

And that store was Cousins.

Cousins was one of several stores packed floor-to-ceiling with the recorded music boomer boys craved. Alexanders basement record department, along with Spinning Disc and Music Makers, all sold the 45s and LPs that changed the world.

But Cousins was very different. Its window showcased all manner of boy-pleasing accessories. A revolving lamp, which — as it turned — showed the flight of a farm boy’s pee into a pond, delighted the pre-teen me. But even that treasure paled in comparison to the row, upon row, of sharp-bladed cutlery.

There, out for all to see, in the window of a Fordham Road store, were battle axes, dress swords, rapiers, scimitars, switchblades, Bowie knives, and gravity knives, of which my beloved K55 held center stage. All were for sale.

After weeks of deliberation, I worked up the nerve to buy my knife. One Friday, after school, I walked down the hill to Cousins, spied my prize in the window, and opened the door.

The store’s ground floor selling space pulsed with hormone-addled teenagers. The guys were all about the Brylcreem, white tee-shirts, black jeans and low-top Converse sneakers. The girls rocked spray-on blue jeans, white Keds, and tight pink sweaters.

Over primitive speakers, Joanie Sommers, a sultry top-forty singer of the day, crooned: “I want a brave man. I want a cave man. Johnny, tell me that you care, really care, for me.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wcLXs3Np93s

I knew then I was in way over my head, but I pushed myself to walk upstairs, where the home furnishings — and cutlery — were sold.

The section was empty, except for the single salesman who idly snapped his jaw and blew smoke rings at the end of the glass counter.

I summoned shallow reserves of sixth-grade nonchalance and breezed casually to the thirty-foot long knife display. There they were, so close, after ogling them from afar, in the street-level showcase window. The long, thin stiletto blades of the pearl-handled switchblades glistened under the lights. I felt faint to think of one of these in the hands of a feared Ducky Boys or Fordham Baldies gang member.

I pushed on, past massive, stag handled hunting knives, to the tray of deadly K55s.

“Help you?” the seedy, bald-headed salesman asked as he ambled over in a maroon Banlon shirt. He nubbed out his Pall Mall in a large, white ceramic ashtray. In its center was the molded figure of a nude woman in a sun bonnet, lying face down, her legs akimbo.

I gulped and took a deep breath. “K55. German,” I sputtered. Silently, the salesman opened the case and, with profound ceremony, pulled a velour tray of K55s. He opened one and, as he did, I heard the steel lock click into place. The knife was now ready for business.

He held it out to me for inspection. With great reverence, I took the knife by the handle and hefted it. I operated the lock and closed, then opened, then closed, the knife. It was, to me, a model of precision German engineering, with a razor sharp carbon steel blade that measured just under the four-inch New York City regulation.

“I’ll take it,” I said, in a whisper. I pulled a wad of singles out of my pants, paid, and put the change carefully in the coin pocket of my Wrangler jeans. The transaction concluded with the startling bell of the store’s cash register.

It needs to be done within purchase cheap cialis icks.org the supervision of the licensed, experienced health professional. However, it can be disastrous female viagra samples for the plant. The characteristics of Kamagra Oral Jelly correspond to the same in tablets, generic levitra or any brand of medication that contains PDE5-inhibitor, these enzymes are destroyed slowly and gradually, curing the impotence in men. It is advised to have only one pill a day means that when the opportunity arises you will be ready. look at here now cialis sale

It was done. I — an eleven year old in P.S. 86 — owned a deadly weapon. A for-real German K55.

But not for long.

First, I accidentally punctured my index finger with the K55s blade tip while practicing my quick-draw, flick-to-open move. Luckily, no one was home, for it took fifteen minutes of compression to staunch the bleeding.

The very next morning, a neighbor saw me flip the opened knife into the dirt while walking Topper, my dog. I was entranced by the fine balance of my K55, and kept flinging the knife down into the weeds across the street from my house, while holding Topper’s leash in my other hand.

The neighbor called my father, and that was all she wrote.

“Where did you get it?” he bellowed.

I looked down at my feet. “Cousins,” I mumbled.

“Get your jacket.”

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Where d’ya think?” was his reply.

We marched all the way down Fordham Road to the store, and stopped. He held out his palm and wiggled his fingers. I handed over my German K55.

“You wait here,” he said. “Do not move.”

I have no idea what he said, or how he said it, but my six-foot four, two-hundred thirty-five pound dad, a World War Two sergeant, got an immediate refund for my jet-black K55.

“You are not to go into this store ever again,” he said, as came out of Cousins and zipped up his jacket. “Are we clear?”

“Yes sir.”

“I’m hungry. Let’s get something to eat,” he said.

Together, we walked up the hill in silence, had two franks with mustard and kraut at Gorman’s, and never spoke of the matter again. Adulthood would come,all too soon, to me and my friends, but not by way of a black, German-engineered gravity knife.